Source: The Straits Times, Feb 19, 2010

[Updated 5 Jun 2012: Lim Hock Siew, Singapore’s 2nd longest-held political detainee, dies]

From student activist and PAP campaigner to Barisan Sosialis leader and second longest-held political detainee, Dr Lim Hock Siew’s story mirrors Singapore’s tumultuous history. Now 79, he bares his thoughts and feelings about his political past.

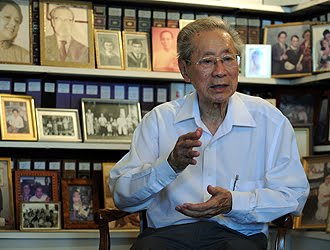

Dr Lim at home, surrounded by family photos. He met his wife, who is a kidney specialist, when they were working together at SGH. Their son was only five months old when Dr Lim was detained in 1963. — ST PHOTO: AZIZ HUSSIN

IT IS a sweltering day as you walk by the row of repainted shophouses along Balestier Road.

As you push open the glass doors and duck inside for a welcome draught of air-conditioning, you meet a group of elderly patients waiting expectantly to see their family doctor.

The name on the door plate of his office may not ring a bell for the young but to older Singaporeans, it jumps right out of Singapore’s turbulent political history: Dr Lim Hock Siew.

Enter his simply furnished room, and you see him at a desk stacked with books, stationery and newspapers. An eye chart is pasted on a glass cabinet displaying photos of him as a dashing young man.

The 79-year-old doctor, in his white long-sleeved shirt, greets you with a soft, occasionally wheezing, yet otherwise firm voice. He is not in the best of health, having suffered kidney failure last year and taken a six-month break to recuperate.

As he is undergoing dialysis three times a week, he would have preferred to extend his break except that his clinic partner, Dr Mohd Abu Bakar, 76, was overwhelmed by the patient load.

So he returned to half-day work last month, seeing around 30 patients every morning, and plans to do so as long as his health permits. ‘It’s kind of an ethical obligation to look after them, and I can keep myself mentally occupied,’ he says.

The name of his clinic harks back to his socialist days as a political activist, first with the People’s Action Party (PAP) and then with its arch rival, Barisan Sosialis. It is called Rakyat, which means ‘people’ in Malay. It was set up by Dr Lim and fellow Barisan Sosialis leader Dr Poh Soo Kai in 1961.

Its consultation fees are no different from other clinics’ – $20 to $30. But Dr Lim charges a reduced rate for poorer patients and gives free treatment to the neediest. ‘I don’t deny help to those who need it,’ he says.

Dr Lim’s sense of compassion and empathy for the poor is well known. At a time when the unprofessional and unethical practices of some doctors are hogging the headlines, the mere mention of Dr Lim’s name evokes hushed respect among his peers.

Even pro-PAP Singaporeans who would be horrified by the prospect of a Barisan Sosialis government admit to having a grudging admiration for Dr Lim as a man who has the courage of his convictions.

Dr Vivian Balakrishnan, Minister for Community Development, Youth and Sports, once singled out Dr Lim as a politician he admired for his strength of character and ability to sacrifice for his beliefs.

Like many of his former leftist colleagues, Dr Lim feels compelled to give his side of the story before time runs out.

In recent years, a cottage industry has sprung up providing alternative histories of Singapore. Books included memoirs by former communist underground leader Fang Chuang Pi, former Barisan Sosialis leader Fong Swee Suan and former Parti Rakyat Singapura leader Said Zahari. Just three months ago, the Fajar Generation, a book on the University Socialist Club (USC) of the then-University of Malaya, was launched.

In a nutshell, Dr Lim’s is a story of how an idealistic student activist joined and campaigned for the PAP in the 1950s and then fought against the ruling party in the 1960s and paid a very heavy price for his beliefs and convictions.

In 1963, he was arrested under Operation Cold Store and detained without trial for nearly 20 years before he was released in 1982.

A Home Affairs Ministry statement on his release had said that he was arrested under the Internal Security Act for his involvement in Communist United Front (CUF) activities.

Dr Lim refused to agree to any conditions that would have granted him early release and ended up in the record book as the second longest-held political prisoner after his leftist colleague Chia Thye Poh, who served 23 years.

Today, 28 years after his release, he still dreams of a socialist Singapore in which there is no exploitation of workers and the oppressed.

Political awakening

BORN in 1931 to a poor family, Dr Lim spent the 1942-45 war years helping his father sell fish in the Kandang Kerbau market. Both his parents were illiterate, but they encouraged their 10 children to study.

He was the only English-educated child in his family. As the top boy in Rangoon Road Primary School, he gained entry to Raffles Institution (RI) in 1946.

It was in RI that he picked up a book by the first prime minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru and became inspired by his socialist ideals.

Going on to study medicine at the then-University of Malaya here, Dr Lim lapped up the works of philosopher Karl Marx and economist Adam Smith, and books on the British Labour Party and Mao Zedong’s communist struggle in China. His political awakening was heightened by the anti-colonial struggles raging around the world.

As he recalls, most of the university students then were indifferent to politics. They were afraid of being arrested and preferred to pursue degrees and jobs.

As one of the best and brightest of his generation, he says he felt a deep, patriotic obligation to do something for Singapore and its people in the struggle against the British colonialists ruling Singapore.

He plunged into campus activism, becoming a founding member of the anti-colonial USC, which was formed in 1953.

In 1953, Dr Lim met the young Cambridge-educated lawyer Lee Kuan Yew, who was helping to defend eight USC students charged by the British for sedition because of an article in the USC’s journal, Fajar.

They won the case and Mr Lee was acclaimed as their champion. The USC rallied behind him and his associates when they set up the PAP several months after the sedition trial.

Noting that the party’s original Constitution showed every mark of a socialist, anti-colonial party, Dr Lim recalls that the USC members went around persuading various groups to support the PAP. The 1955 elections saw the 24-year-old Dr Lim stumping for PAP at mass rallies.

PAP was then identified with the working class and Chinese-speaking masses. But the facade of unity maintained by the motley crew of English-educated intellectuals, Chinese-educated socialists, professionals and trade unionists could not last.

The ideological differences began to surface. One episode in 1957 that stuck in Dr Lim’s memory was the plot by a group of radical unionists within the party to oust PAP strongman Ong Eng Guan and several others from the PAP leadership. They opposed Mr Ong as they viewed him as anti-left and an opportunist.

He felt then that the move was ‘most unwise’ as it would create party disunity and provoke a crackdown by the colonial government.

As he recollects, he and several USC members tracked down three of the prime movers – Mr Chen Say Jame, Mr Goh Boon Toh and Mr Tan Chong Kin – and sought to dissuade them. They failed. Dr Lim believes that what he did then probably aroused Mr Lee’s suspicions that he was in cahoots with the leftists.

The central executive committee (CEC) elections resulted in a deadlock with six seats going to the Lee group and the other six going to the leftists. Shocked by the humiliating defeat of his associates, Mr Lee refused to take office. Dr Lim says he tried to persuade him to do so – to no avail.

As it turned out, five leftist CEC members were arrested by the Lim Yew Hock government in an anti-communist operation – and Mr Lee and company were able to regain control of the party.

In 1958, they introduced a ‘cadre’ system in which only appointed members could vote for the CEC. This marked the beginning of the leftists’ disillusionment with Mr Lee, says Dr Lim.

Break over merger

WHEN the 1959 elections came around, Dr Lim says he and Dr Poh offered themselves ‘in good faith’ as PAP candidates. The answer was negative. ‘He did not trust us,’ says Dr Lim, referring to Mr Lee.

After the historic elections which swept the PAP to power for the first time, Dr Lim discovered that his party membership was not renewed.

From the sidelines, the government doctor witnessed the increasing acrimony between Mr Lee’s group and the leftists which was to lead to what is called the Big Split of 1961.

The two factions were locked in a monumental struggle over the issues of merger with Malaya, Chinese education and the continuing detention of students and unionists.

Racked by dissension, the PAP was on the brink of collapse after losing two by-elections in Anson and Hong Lim in 1961.

Concerned over the leftist challenge within his party, Mr Lee moved a motion of confidence in the 51-seat legislative assembly. The PAP survived when 27 voted aye but 13 dissident assemblymen abstained.

Expelled from the party, the dissidents formed Barisan Sosialis with other defectors from the PAP in August 1961. The party was led by Mr Lim Chin Siong.

It was at this juncture that Dr Lim joined the new party. He had to give up a scholarship for further study and quit the civil service.

The Barisan Sosialis then, he recalls, was a very formidable organisation filled with thousands of dedicated people and ‘scores upon scores of university graduates’, ready to form an alternative government.

As a CEC member, Dr Lim helped to run a ‘brain trust’ which consulted a group of more than 50 graduates from the then-Nanyang University and University of Malaya and prepared position papers.

‘We didn’t have a lack of talent. We had more talent than we wanted,’ he says.

In his recollection, the biggest issue that divided PAP and Barisan was merger with Malaya to form Malaysia.

Fearing that Singapore would fall to the communists, Malayan Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman had proposed on May 27, 1961 that Singapore, Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei merge with Malaya to form the federation of Malaysia.

Singapore would have 15 seats in the federal house of representatives, less than what it was entitled to on the basis of population ratios, but a debatable trade-off for Singapore’s exclusive autonomy over labour and education.

Although the leftists were committed to the ultimate goal of unification between the peninsula and the island, they argued that these terms for merger would make Singaporeans ‘second-class citizens’.

The main sticking point, as Dr Lim points out, was that there were ‘two sets of citizenship: one for Malaysians and one for Singaporeans. Singaporean citizens could not participate in Malaysian politics, much less be proportionally represented in the federation’.

The battle between both parties reached its culmination during the referendum on Sept 1, 1962, in which the PAP Government cleverly devised three alternatives for merger on varying terms with no option to say no.

PAP won by a large margin, with 71 per cent of votes in favour of its ‘Alternative A’ against just over 25 per cent who cast blank votes, which the Barisan called for to protest against the ‘sham referendum’.

Imprisonment

THEN came the big crackdown. On Feb 2, 1963, more than 100 leftists and unionists were arrested in a massive security exercise known as Operation Cold Store, aimed at putting communists and suspected communists out of circulation.

On the mass arrests which changed the power balance in Singapore irrevocably, Dr Lim reflects: ‘We lost not to Lee but to the British, who crushed the leftists for strategic, not security reasons.’

When he speaks about his nearly 20 years in detention, there is an edge to his otherwise calm voice.

Year after year, he recounts, attempts were made to break the spirit of prisoners through solitary confinement and interrogations, to make them confess their involvement in communist activities.

Dr Lim became a counsellor of sorts to the prisoners, encouraging them to talk about the physical and psychological abuse they faced during their interrogations. Some broke down in tears as they relived their experiences.

In March 1972, Dr Lim released a statement about his detention and his experience in being taken to the Internal Security Department (ISD) headquarters on Robinson Road two months earlier. He had insisted on being released, saying that ‘history had vindicated my stand’ that the 1963 merger would not work.

He says that ISD officers wanted him to issue a public statement that he was prepared to give up politics and devote his time to medical practice, and to express support for parliamentary democracy.

Dr Lim demanded to be released unconditionally, saying that he should not need to give up politics if there was parliamentary democracy.

He says that he was asked to ‘concede something’ so that his long detention could be justified. He replied that he was not interested in ‘saving Mr Lee’s face’, and would not issue any statement to condemn his past political activities, which he said were ‘legitimate and proper’.

When asked for the Government’s response, a Ministry of Home Affairs spokesman says: ‘Contrary to Lim Hock Siew’s claims that he was an opposition politician carrying out ‘legitimate and proper’ activities through the democratic process, Dr Lim was in fact a prominent Communist United Front leader who, along with other CUF leaders, had planned and organised pro-communist activities in support of the Communist Party of Malaya, which employed terror and violence in their attempt to overthrow the elected governments of Singapore and Malaysia.’

In 1978, Dr Lim was released from detention and placed in Pulau Tekong under certain restrictions. A government statement had described him as a CUF member who refused to give a written undertaking that he would not be involved in communist activities and renounce the use of force to change government.

Dr Lim’s view was that since he had never advocated violence, he should not have to renounce it. ‘It’s like making me sign a statement that I would not beat my wife,’ he says.

He spent four years on Pulau Tekong before it became an army training area. There, he read medical books and became the only doctor for the few thousand villagers on the island. In appreciation, grateful villagers would ply him and his wife with durians, prawns and fish.

Release

FINALLY, on Sept 6, 1982, the Government allowed him to live on Singapore island, on the understanding that he would concentrate on his medical practice and abide by various conditions.

Asked how he coped with the long incarceration, he puts it down to an unshakeable conviction that his political stance is right.

‘We were the leaders of the main opposition party, supported by the workers in Singapore, and we cannot betray our supporters. So we stuck to the bitter end. It’s a matter of intellectual integrity.’

Would he shake hands with Mr Lee? His reply: ‘It is for the oppressed to be magnanimous, not the oppressor. I’ll forgive him and shake hands with him if he admits to his error and apologises to me and my wife.’

Dr Lim’s wife Beatrice Chen, who is a nephrologist or kidney specialist, helps to treat her husband. She declines to be interviewed as she shuns publicity.

They met in 1958 when they were working together at the Singapore General Hospital, and married in 1961.

Dr Lim was detained two years later. For the next 15 years, they saw each other for half an hour each week, separated by a glass panel, and spoke by telephone.

‘The fact that we can see each other is a relief,’ he says. ‘Our common struggle was a unifying force. We understood each other. She kept on encouraging me, giving me moral support…it was very hard for her. She’s a great woman.’

The couple have one son, who is now working in the National University of Singapore. ‘He was five months old when I was arrested. When I came out, my wife was in menopause. I missed the joy of bringing up my own son.’

When Dr Lim is not seeing patients, he catches up on current affairs, surfs the Internet, and reads political philosophy – currently, Bertrand Russell’s A History Of Western Philosophy. He also paints as a hobby.

Step into his condominium home off Mountbatten Road, and you will be greeted by a visual feast of paintings – of scenery, flowers and women – all strictly non-political.

But one has a Chinese couplet which reads: Befriend a thousand books, and have the spine to stand by your beliefs.

More reports on Lim Hock Siew:

Recent Comments